By Arnold August, Exclusive for Trabajadores

In theory, the Canada Labour Code grants unionized workers the right to strike. Recent Supreme Court decisions not only entrench this right, but also protect it under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Constitution.

However, how does this work in practice? Let’s take a recent example.

However, how does this work in practice? Let’s take a recent example.

Don Foreman — a member of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) who has been active in the labour movement nationally and internationally (Cuba and Venezuela) for 36 years — told me in early 2019, in an online interview for this article, that the CUPW had given notice to Canada Post, the government-run postal service, to begin bargaining.

After eight months of bargaining in the hopes of reaching a collective agreement, with no action on the part of Canada Post, he said that “our leaders asked us for a strike mandate, which was given with 93% voting in favour if an agreement was not reached.”

On 22 October, the CUPW members exercised their right to strike in an effort to reach a collective agreement with Canada Post that responds to the workers’ concerns.

Was the union strike action reasonable?

From the outset, the union was very reasonable in its actions, mindful to avoid totally disrupting mail delivery. “So as to limit the impact of the strike on the public sector,” Don tells us, “our union opted for a rotating strike strategy, beginning with one local walking out each day. There was only one small interruption of service during the five weeks of the rotating strike process.”

On November 22, the Liberal government reneged, after having given the workers its word, and forced them to return to work using the stratagem of a fast-track legislative process, whereby debate in the Canadian Parliament was shut down. At the eleventh hour, on November 23, the bill was passed in the House of Commons and sent to the Senate. On the November 26, the Senate passed bill C–89.

What was the union’s reaction?

“Although we could have challenged this unquestionably illegal and unconstitutional bill, we returned to work on November 27, ceasing all our strike actions.”

This calls for some clarification: the right to strike is an indispensable component of collective bargaining. “When good-faith bargaining breaks down, one fundamental way for us to play a meaningful part in achieving our collective labour objectives is to collectively stop working and withdraw our services.” Indeed, it is for precisely this reason that the right to strike is constitutionally protected as a component of freedom of association, which is guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.

The “right to strike” in capitalist countries: a concession to avoid revolutionary change?

Let us go back and situate the “right to strike” in historical context for Cuban workers, so that we can further appreciate its precarious and hypocritical nature under capitalism.

A strike is a work stoppage, a collective action undertaken by a group of workers that consists of a temporary cessation of work; that is, a total or partial refusal to carry out the work for which they are responsible. Normally, it is used as a means of exerting pressure on the employer during bargaining, so as to obtain better wages or, in general, better working conditions, although it may also involve a protest with repercussions for other spheres or sectors.

Strikes took on importance with the industrial organization of labour, in which large groups of workers experiencing similar conditions and physically grouped together in a shop or mine could, for the first time, organize their actions as a homogeneous group.

In the early years of the Industrial Revolution in England, the right to strike was severely punished, even treated as a crime. Subsequently, it came to be treated more tolerantly; governments decriminalized strikes, but continued to treat them as a failure to fulfil one’s labour obligations.

Thus, one can conclude that the “right to strike” in the capitalist countries is a concession that the workers have won from the ruling circles and their governments through difficult and self-sacrificing struggle. These concessions are made to avert a worse scenario for the capitalist system: a general revolt by the oppressed majority against the oppressing minority. However, this “right” can be taken away at any time, as we see in the CUPW example.

Were the Canadian union’s demands reasonable?

Therefore, the “right to strike” in the capitalist countries is similar to their highly promoted “freedom of the press and expression.” It is “permitted” as long as it does not challenge the status quo, nor even the short-term goals. What unmet demands by the workers forced them to strike? The goal was very far from revolutionary change. On the contrary, their short-term demands were quite reasonable and also included improvements to the postal service — a target of much criticism by the Canadian public as a result of neoliberal cutbacks over the years by both Conservative and Liberal governments. These are some of the demands, according to Don:

- Extend full job security to all regular employees.

- Restore door-to-door delivery to all locations where it was abolished as a result of neoliberal cutbacks.

- Provide a significant wage increase with full retroactivity and a cost-of-living allowance.

- Improve benefit plans, including the dental plan, the extended health care plan, the vision and hearing plan, and life insurance for both active employees and retirees.

- Improve maternity, parental, and compassionate care leaves.

Yet, the right to strike was arbitrarily taken away by rushing a bill through Parliament with virtually no debate in this “paragon of democracy.”

The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919: lessons 100 years later

The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919: lessons 100 years later

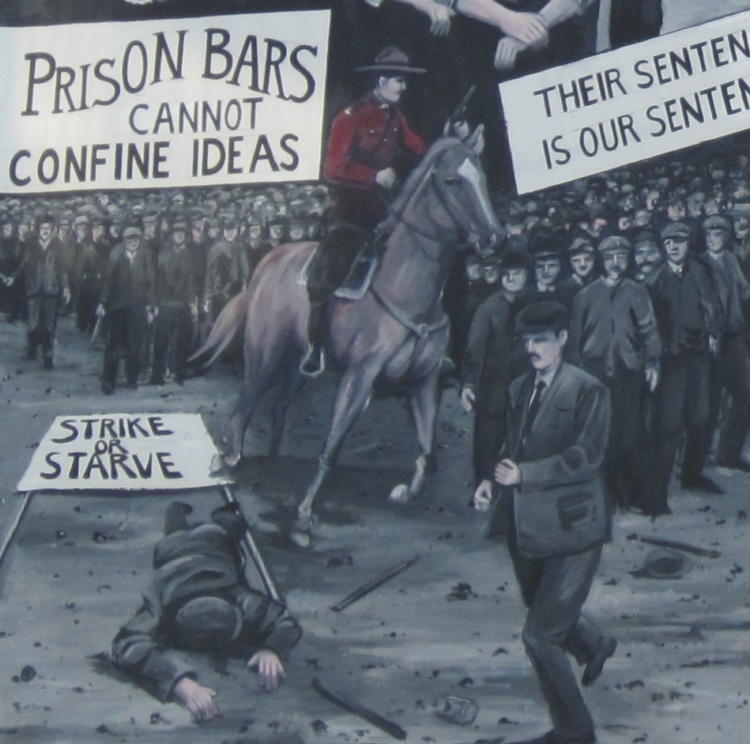

This year in Canada, we celebrate the centenary of the Winnipeg General Strike, one of the most iconic and emblematic workers’ actions in Canada’s labour history since the end of World War I.

In the aftermath of that war, due to the postwar recession, poor working conditions, the presence of radical trade unionists, and a large influx of returning soldiers, 35,000 citizens declared a strike in May 1919 — known ever since as the “Winnipeg General Strike.”

After several arrests, deaths, deportations, and violent incidents, the strike ended on June 21, 1919 when the mayor read the Riot Act and a group of Mounties charged a group of strikers. Two of them died and at least 30 were injured, and that day came to be known as “Bloody Saturday.”

It is a reminder to workers in Canada and the other capitalist countries, such as the US and UK, the rest of Europe, Australia and New Zealand. These “rights” can be crushed at any moment, as we see in the case of Julian Assange. “Rights and freedoms” under capitalism are extremely limited when it has reached the stage of imperialism, and thus becomes even more ferocious as it extends its war-mongering tentacles for world domination. Make no mistake about it: we Canadians know. Our country is part of this imperialist system, as its nefarious pro-Trump role in Venezuela shows. Moreover, Canada claims to oppose the Trump policy of hardening the sanctions against Cuba with Washington’s full application of the Helms-Burton law, yet at the same time, Canada acts as the very vanguard of the Lima Group in imposing devastating sanctions and regime change policies on Venezuela. This is a policy, as we in Canada know, that also has Cuba in its sights! So what kind of opposition is this to the most recent Trump policies?

Rights in Canada and Cuba: Converging for May 1… again!

The open and disguised enemies of the Cuban Revolution, both inside and outside the island, propagate a preconceived idea based on the US-centric notion that Cuba has to “change” and adopt what they consider to be universal values, such as the rights we are talking about in this piece. But have they forgotten that Cuban workers before 1959 often had the “right to strike,” yet their actions and leaders in the union and the Communist Party were repressed and assassinated?

Since the Cuban Revolution was initiated 60 years ago, peace has finally come to the working class and small farmers. They are now part of a different system, and not in opposition to the status quo as they were before 1959. They thus have the luxury — despite the economic hardships caused, in the main, by the US blockade since 1961 — to deal with problems in a non-antagonistic manner based on social solidarity, as an integral part of the Cuban collectivity.

This hallmark of present-day Cuba may very well be the reason why workers and their organizations flock to Cuba every May Day to experience once again what it means for workers to live and work under socialism.

This year there is an added incentive for Canadians to attend: it will surely be an occasion to express solidarity with the Bolivarian Revolution and the workers who are in the forefront of defending it, a recent example being their amazing efforts to restore the electricity grid.

Canadian workers and their unions can proudly show up in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución on May 1 with their heads held high. After all, over 5 million Canadian workers have had the opportunity to express themselves through their unions in support of Venezuela’s right to self-determination and Maduro’s right to govern as the country’s legitimately elected president. This was carried out despite the mainstream media and academics’ almost daily pressure since January 23, 2018, calling Maduro’s election “deficient,” hampered by “electoral irregularities” and “jiggery-pokery,” and terming him “authoritarian” or even a “dictator.”

Thus, on the eve of May 1, let us honour the workers of the world as being in the very vanguard of opposing disinformation and defending the rights of workers in capitalist countries, with Cuba and Venezuela as their example and inspiration.