Abelardo Estorino, the indispensable dilettante died guarded by his memories, books, pictures and different objects marked by the time: “I do not throw anything out, because they are things I love, they are memories that go together with my life. If I think like that, in one way or another, my works also reflect they way I live, he once said in an interview.

Abelardo Estorino, the indispensable dilettante died guarded by his memories, books, pictures and different objects marked by the time: “I do not throw anything out, because they are things I love, they are memories that go together with my life. If I think like that, in one way or another, my works also reflect they way I live, he once said in an interview.

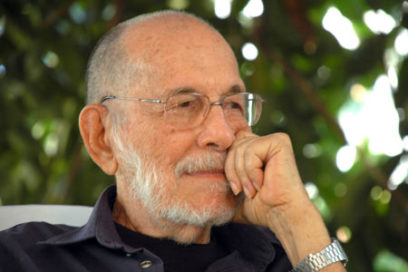

The first playwright who was homage by the International Book Fair died at home and since then, all the media has devoted a space he deserves. He did not like to be in close-up shots, but his work placed him there and now his death has sown him for good in the Cuban culture’s pantheon.

He was a modest, shy man who used to flirt with time. In his plays he broke with the rigidity of chronology. He moved his characters as they fit in the story he told. He disrespected time and in change, it was indulgent giving him a long life. He lived 88 years.

He was born in 1925 in Union de Reyes, Matanzas province of Cuba. He lived in a world is a “madness”: “I do not know if man will be able to change violence,” he said, “but we have to make an effort to walk in favor to the good things.”

Estorio arrived at the capital of Cuba in 1946. He came to study dental surgery, a specialty he devoted little time of his life, because the fact to share the house when he was young with the painter Raul Martinez and the playwright Rolando Ferrer definitely changed his life: “I joined that world, but people from the theater saw me as the one stuck. I was a dilettante interested on the theater.”

Some of his works were: Hay un muerto en la calle, inspired on Eduaardo Chivas and the political gangsterism during the administration of President Carlos Prio; El peine y el espejo in 1960. His best opportunity was with El robo del cochino that granted him a mention in the Literary Award of Casas de las Americas in 1961.

“All my works are devoted to rummage inside the human being and its internal conflicts.” He reflects the disintegration of the families, endemic male chauvinism in his plays. He debates the rolls associated to gender and he likes strong feminine characters and some examples are in El robo, La casa vieja, Vagos rumores, Parece blanca and others.

His style developed from the called “realistic theater” up to include innovated formulas where he explores behaviors of the vanguard and the experimentation. They are present in La dolorosa historia del amor secreto de don Jose Jacinto Milanes and in Morir del cuento.

His plays were performed in Czecoslovakia, Norway, Sweden, Chile, Venezuela, Mexico and the United States (U.S.); this last one did not allow him to return, despite his success in New York and Miami. “They did not allow me travel to the U.S. again, after I signed a letter against fascism together with other dozens of intellectual people,” he once said.

Estorino was academician from the Language Cuban Academy and was granted the Distinction for the Cuban Culture, the one of the National Literature in 1992 and of Theater in 2002.